On Fear & Motivation: KattiJo’s Rookie Iditarod ’22

I. Fear

(Like all rookies, I assume) I felt nervous in the weeks and days leading up to the start of my first Iditarod. I doubted my own abilities, and those of my mostly inexperienced team. I stressed about how to dress and how to pack for two weeks of spring time weather fluctuations across 1,000 miles in Alaska. I wondered what would happen if I broke my sled. Could I engineer a fix by myself? How would I deal with extreme sleep deprivation? How would I fare physically through those notoriously tricky driving sections of The Happy River Steps? The Gorge? The Burn? Would I lose my team? How/would I be able to get them back? What injuries would they incur during our time apart? Could I fit more than one dog in my sled if I needed to load a couple instead of one? In short, I feared the unknown, and everything was unknown to me.

KattiJo leaving the official start line of Iditarod 2022

Sunny and warm in the hills between Elim and White Mountain

Cold morning sunrise on the way to Unalakleet

Going into the race, the advice I heard repeatedly was this: Once you leave the start line, all of the fear will fall away and you’ll simply be doing what you already know how to do – just running your dogs. Unfortunately that advice turned out to be wrong for me. The fear stayed with me throughout the entire race, riding my shoulder as an unwelcome passenger.

That is not to say that I didn’t have fun on the Iditarod. I absolutely did. And those scariest sections of trail that I feared most ended up being some of the most joyous and proudest moments of my race. Too bad the pride of tackling and surviving one intimidating section did not eradicate the fears I had about the upcoming sections! So the fear stayed…

Feeling pretty nervous running through the dreaded Farewell Burn… But at the same time, I find myself actually having fun!

I also smelled like fear. Did you know that “fear sweat” has its own distinct smell? Well it does, and I totally reeked. I couldn’t even stand the smell of myself! The fresh, wild, open air was my only salvation. The short sleeps in small, overheated checkpoint shelters added to my stench and I literally cursed myself at least once an hour for not packing a small thing of deodorant alongside my toothbrush and chap stick. I mostly forgave myself for being scared, generally speaking. I chalked it up to being a normal emotion, and well within the typical range for my ironically risk-averse personality. But now I also had to live with the retched smell of my fear all around me.

One reprieve from the fear came in those too short, although somehow very restful sleeps. I can only explain the lack of mushing nightmares in my dreams as my brain’s way of coping with the stress. Perhaps I was making up enough “worst case scenarios” in my waking hours that I didn’t need to come up with any more in sleep.

Getting ready for a nap in McGrath

From start to finish, no matter how many times you’ve run the Iditarod (I assume), there is a constant internal dialogue with oneself titled “Things I’ll Do Differently Next Time.” Obviously deodorant was at the top of my list. But the simple fact that I was even making a list for next time is noteworthy for any rookie. Although my clearest thought throughout most of the race was something like “Yes, I think I would do this race again; there is enough joy here. But I don’t know that I will, because there is also enough fear.”

II. Motivation & Flow

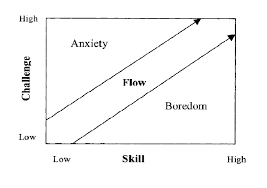

So why run the Iditarod at all? And why consider doing it again? I spent many hours on the trail contemplating this question, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of Flow came back to me. I first encountered this theory as an undergraduate in Recreational Therapy at UW-La Crosse, and somewhere between Finger Lake and Rainy Pass I was able to re-create this graph in my mind:

The simply principle is that as one’s skills increase in a particular area, the challenge of performing that skill must also increase to produce something called Flow. A person is in Flow when their skills perfectly meet the challenge presented to them. You know you’re in Flow when you lose track of time, forget anything other than the immediate act of what you’re doing, and find pure bliss in the activity. Being in Flow may also be referred to as being “in the Zone.” To read more about Csikszentmihalyi and the theory of Flow, check out this webpage: https://positivepsychology.com/mihaly-csikszentmihalyi-father-of-flow/#Mihaly-Csikszentmihalyi

After nearly 12 years of dog mushing, running the Iditarod presents one of the last great challenges to my abilities. Bored with my home trail system and uninspired by shorter races, I was looking for Flow by running 1,000 miles across Alaska.

Flow achieved! Completely blissed out on this sunset section of trail outside of Kaltag.

And I found it. The Gorge and The Burn were more beautiful and breathtaking than I ever could have hoped. I nearly strained a muscle patting myself on the back for getting through them alive and smiling. The pure love, respect and gratitude that I felt for my single lead dog, Chippewa, in those miles was something that I will never be able to adequately describe to anyone who isn’t a musher. And my heart welled with pride in him again as he single-led through a blizzard into McGrath, then in and out of Unalakleet on ice so slick and treacherous that I was stunned to understand such a thing even existed. Leaving Koyuk, Chippewa’s sister Yentna took over in lead and she and Knox led through an out-of-nowhere windstorm during which I was hard-pressed to see any trail markers in the dark and blowing snow. But they saw them, and never hesitated to keep us moving down the trail. This was all Flow for me and my team. We were put into situations for which out skillset was totally challenged, but also miraculously suited.

But the Iditarod is 1,000 rugged miles of wilderness, and we weren’t in Flow the entire time. Times not spent in Flow fall into two categories: Essentially that which is too easy, and that which is too difficult. In the former category (too easy) were those straight and flat miles of the Yentna and Yukon Rivers, as well as the never-ending moguls between Tin Creek and Nikolai. All a bit too easy, and downright excruciating when the boredom was coupled with sleep deprivation. The side-sloped sections of trail between Unalakleet and Old Woman cabin could also be described this way. Doable, but not nice.

Soooo thankful to finally be in Nikolai after 40+ miles of moguls to get there. The Iron Dog snowmachine race, coupled with a LOT of snow, created perhaps the worst moguls the trail has ever seen. These continued on and off, all the way to the coast.

Beyond happy to be finally be approaching Kaltag and leaving the Yukon River.

Old Woman cabin. Not officially a checkpoint, but a popular resting place for mushers halfway between Kaltag and Unalakleet. The side-hills and sleep deprivation on the way here were a wicked combination!

In the latter category (too hard) I would put The Steps – especially that last one – as well as the run into Ruby. Leaving Cripple was fun, but before long Jeff and I were in a pretty serious wind storm, with at least one snow drift that must have been 15 feet high. Plummeting straight off the rip-curled backside of that thing elicited a real, true scream from me. Things did not get easier as we neared the checkpoint. With Jack in my bag (head poking out, of course) we navigated a ridge line, full of steep and icy side-slopes. I worried constantly that with one false, tired move I could tip the sled, and send Jack, myself, and the entire team sliding down the side of the mountain. Luckily that didn’t happen, but I did manage to tip the sled around a 90 degree corner on an icy, plowed village road once in Ruby. I lost the team, and was immediately overcome with feelings of failure and self-doubt. I also re-kindled a long-smoldering fear of mine: getting in and out of checkpoints.

Jack. My sweet passenger on the way to Ruby. Thankfully he and the entire team were totally fine when I found them! After dumping me off at one intersection, the sled righted itself, but tipped again around a second intersection. That time it stayed tipped, and the snowhook bounced out, eventually catching a snowbank on the side of the road.

Finally, in the “too hard” category, was the run from White Mountain to Safety. I’ve already written about extensively about the wind storm, so I won’t recap it here. The only thing noteworthy in this context, is that I don’t generally view this event as something beyond my skill level. Instead, I prefer to frame it as the “once in 40 year storm” as it has been described. Instead of wondering how I could “do it differently next time,” I prefer to believe there won’t be a next time.

*Side note: One piece of advice that was given to Jeff and I in the weeks and months after the wind storm, was to figure out a way to “drop” our sled bags. A regularly-hung bag can essentially create a triangular “sail” in strong wind. In a cross-wind, this sail can be a major factor in what causes a sled to tip over and roll. It’s possible that if we had been able to drop our bags to a lower hanging, or flat, position, they would not have caught the wind, and we would not have tipped and tumbled off the trail. So that’s at least one “skill” I could use in the future!

Jeff and I in White Mountain

III. Iditarod 2023

As I write this recap of my 2022 Iditarod, I have just signed up for Iditarod 2023. Why?

1 – More Flow. While it sometimes feels as if my mushing skills are plateauing (or on my worst days – even regressing!) I know that’s not true. Every time I go out with my team I become a better musher. And the Iditarod still presents one of the last opportunities for me to achieve Flow.

Happy musher on the way to Rainy Pass

2 – Increased Confidence. Iditarod 2022 is still fresh in my mind – the good and the bad. Running a second Iditarod sooner rather than later means I’ll remember more from the trail, which should set me up for smoother runs, smarter decision making and less anxiety overall.

Booting up for the Ceremonial Start 2022. Since I managed to tip my sled TWICE in this 12 mile parade before the “real” race start, the Ceremonial Start of 2023 is sure to give me lots of anxiety…

3 – Fewer Dogs. Unless we rely on running a large pool of Yearlings – which we don’t really want to do – our race pool is pretty small for this coming season. We can only comfortably field one Iditarod team, not two.

Jeff and I and our two teams near Nome, at the end of Iditarod 2022

4 – Less Stress. Having both Jeff and I away from the kennel for the three weeks required for all Iditarod-related events is stressful! Even with the best of helping hands left back at the kennel, there is no real substitute for one of us staying home.

Jeff and I at the start of Iditarod 2022

5 – New Goals for Jeff. With Iditarod off the table, Jeff is looking forward to putting all of his energy and focus on the Kuskokwim 300 and the Kobuk 440. Iditarod can be a big distraction from other races, and a big energy suck, too. Historically Jeff hasn’t felt comfortable with the nearness of the K300 to the start of the Iditarod. And by the time Iditarod is over, he usually has zero energy left for a 440 mile race in early April. This year should be different!

Mushing into Nome at sunset

IV. A Love Note

In closing, I want to mention each of the dogs who ran Iditarod 2022 with me. They were a team comprised of three veterans and 10 rookies. Four of them were dropped along the trail, and nine of them made it to Nome. All of these dogs are eligible to return for Iditarod 2023, with the exception of Whiskey who went to a retirement home in June. That being said, many of the dogs who ran on Jeff’s Iditarod team will also join my team. That means that this same exact combination of 13 dogs will likely not run together again. You were special, because you were my first. I love each of you, and am so proud of you! And I thank you for sharing the trail with me.

Frito eagerly awaits a second fish snack. Leading the team outside of Ophir.

Chippewa and I on top of “Little McKinley” between Elim and White Mountain

Jae Bird

Dylan

Twin boys Jack and Robin

Oyvind is a steady team member, and probably the kennel’s loudest “cheer leader.” When we make impromptu stops on the trail to check booties or take a photo, Oyvind will immediately start barking and “harness-banging,” making it almost impossible to stay stopped. We hate these poor manners during training, but this “go-get-’em” attitude is a joy to have on a long race. Sponsored exclusively by The Linn’s of CA.