Iditarod 2019 Part II of II: McGrath to the Finish

The run from McGrath to Takotna, and then on to Ophir, is smooth and quick in the cool of early morning. The dogs are all feeling well-rested and fresh after their day in McGrath, and only Pogo shows any sign that he has been on the race trail (a few sore muscles that take a couple minutes to warm up as he starts the run). Unfortunately, about midway through this five hour run, both Qarth and Knox have some diarrhea and a moment of an upset stomach. I wonder about the quality of some of the meat in my food drop, after spending over two weeks in plastic at temps right around 30.

As we pull into Ophir, I decide to shut down for a few hours and get the dogs some clear, cold water. Most of the team drinks, including Qarth and Knox, which is important with the loss of fluids from being sick. I give everyone a period of time to lay on the cold snow, and then shake out some straw, making a cozy bed to enjoy the warming sun. Competitors roll by as the dogs rest and I work on chores. Seth and Lev keep moving up the trail to take advantage of the still relative cool. Kristy and Anna Berington are parked next to me in Ophir, both finishing up their 24 hour rest. We chat a little, and then I lay down for a short nap, after giving the team their meal. Knox does not eat, and this bums me out a little.

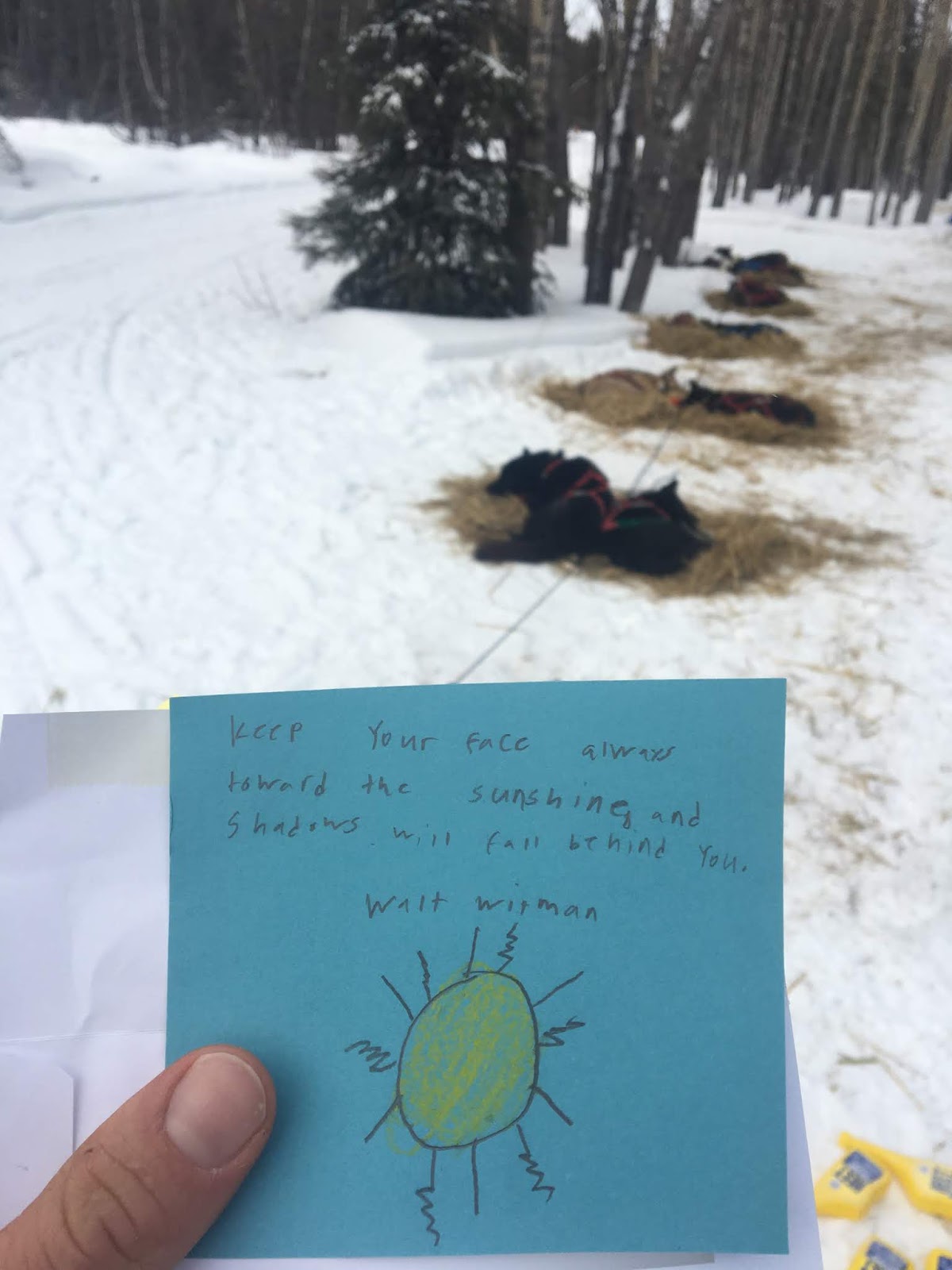

This quote, sent out on the trail by my junior musher friend Caleb,

helped shape my mindset for the next 48 hours.

“Keep your face always towards the sunshine,

and shadows will fall behind you.” -Walt Witman

Pogo wakes up pretty stiff and sore from his nap, and does not immediately warm up with a walk around the checkpoint. I decide that it is probably best for him to fly home, and best for me to not risk having to carry him for the next 78 miles to Iditarod. This turns out to be a good decision, as the trail is incredibly rough and slow to Don’s cabin (the halfway point between Ophir and Iditarod).

We leave Ophir in the hottest part of the afternoon (my second mistake of the race), and the dogs are running through temps of close to 45 degrees, and exposed to brief moments of full sun. It had been breezy and snowy in the forecast, and I can see we are mushing towards dark clouds, but in the moment, I am very much regretting our late morning stop in Ophir. We continue to plod, and Knox comes out of lead to be replaced by Qarth, who until now, has only been pulling at about 60 percent. However, as soon as he is promoted to lead and faces a difficult, slow trail, he turns on the gas and drives forward in a nice trot. The trail, full of soft holes and deep moguls, is by no means pleasant, but Qarth seems to enjoy himself, and his stomach appears to be feeling better. Good boy!

Snow starts to thin out some 30 miles from Ophir, and by the time we get into the exposed hills before Don’s Cabin, we are mushing across sections of grass and dirt. These conditions are somewhat typical for this area, but are very different from the year before, where the dogs and I travelled through a complete blizzard with more snow than a musher could ever want. Now, in late evening, we have easy travelling (the grass and dirt has been, temporarily, left behind) and are enjoying some beautiful views as the sun sets.

Don’s Cabin is a dilapidated shack along the trail, and roughly marks the halfway between Ophir and Iditarod. I have a couple hours of rest planned here, and we pull onto another musher’s used straw, and next to Lev (who is just getting ready to depart). In classic fashion, Lev is discussing the upcoming trail hazards, the prediction of rain, and the general malaise that is day five of Iditarod. The dogs get comfortable while we chat back and forth (both working on chores), and the team eats their meal with vigor, Knox being the exception. I am able to convince him that his beef is good, but meals do not impress him. Because this is where the bulk of his resting calories are supposed to come from (along with his important race supplements), I attempt to trick him into eating it by adding some small chunks of beef. He is on to my plan, and simply picks out the beef from the kibble (which also includes fat, a meat blend, and water). Oh well, I figure, he will eat his meals eventually.

The trail from Don’s to Iditarod is pretty hilly, and I pull out my ski pull only a couple miles after leaving our rest. There are some flakes of snow and a little breeze, and this makes the run a bit more interesting for me as a driver. The dogs are dialed into their program, and are trotting smoothly at 7.5 miles per hour (a near record for us in this race, given the conditions!). We leap frog Richie, who has camped along the trail, and start getting into some rough creek crossings as we get closer to Iditarod (little drops onto the ice, followed by steep embankments on the other side). And then, suddenly, we have left all snow behind, and are mushing through fields of frozen tussocks.

A tussock is a clump of earth and grass, usually found in wet, swampy areas. There is never a single tussock, and they usually form right next to their friends, and fill an entire valley (as in the case of this particular valley that we are currently mushing through). The trail gets incredibly rough, and the cracks between tussocks are almost a foot and a half deep at times. All of my energy is focused on trying to safely walk the dogs through this terrain, while also not catching my foot on a chunk of ground and breaking my leg. I was already a little warm as we approached this area, and now I am sweating. Qarth has been navigating the trail pretty well, but gets into weaving as our speed slows, trying to avoid the worst of the tussock congregations (to no avail). I don’t want the dogs running at any kind of angle through this rough terrain, and decide to make a quick stop, to move Mereen up with Qarth (just to stop him from meandering). They work together in a “straight ahead” direction, and everything is looking good for the moment. We are moving through rolling hills, and I guess that we are still about 10 miles from Iditarod. We were told in the pre-race meeting that the trail would be “a little bare and tussocky” as we got close to Iditarod, so I know that these conditions will only continue. My legs are getting a work out from riding the drag and getting jostled around, and I am alternating between left and right foot. The dogs are pretty enthused about the change in trail conditions, and I am having to put a fair amount of pressure on the drag to keep them under control. Whiskey, who has not really worked until this point in the race, is suddenly giving it 100 percent and barking on the downhills… Asshole!

On one of our slow descents, my drag suddenly feels a little different, and I glance down to see that it has ripped loose from the belt that attaches it to the sled (kind of dangling by a thread at this point). We get to the bottom of the hill, and I make a stop. The dogs get a snack, and I pull out my repair kit with some rope. It is about 4 A.M., so my knot tying skills aren’t exactly on point, but I manage to get the piece of snowmachine track (that is my drag) attached to the brake bar (in a temporary fix). We are back to moving down the trail (a generous term for what we are now running). The concern now, is that every time I stand on my drag with full weight, it also depresses my brake bar, and puts that piece in grave danger of catching on a tussock and being ripped off the sled entirely. So, I am now gingerly pressing the drag and also using my foot to slow the team in any place where it looks at all safe. We continue on.

The banks of the Iditarod River are a welcome sight, and around the bend I can see a few lights of the checkpoint. We pull in at about 5:30, and I get everyone bedded down and analyzed for potential injury. Somehow, every dog has survived the run in 100 percent health, and they appear ready for more once we get a few hours of rest. I get them fully taken care of, and then head up to the “musher cabin” for a couple hours of sleep. I am surprised to see my buddy Wade, sleeping on one of the bunks. I learn a little later that he had a massive sled malfunction on the tussocks, and has spent over 10 hours resting his team and getting his sled, now with only one runner, ready to go. As we get catch up after some sleep, he explains that the tussocks caused his tail-dragger (the portion of sled behind the musher) to catch and just rip right off. It took a good portion of the one runner with it.

I have opted for a solid six hours in Iditarod, a chance for two and a half hours of sleep for me, and two large meals for the dogs. Knox has eaten one of his meals, and a couple of snacks, so I decide he is set to keep moving with the team. His attitude has been good, so I figure if he is having fun, his appetite will eventually catch up. As I am packing my sled, wearing only a hoody and sweatpants (my gear is still in the cabin drying), the clouds produce a gentle sprinkle of rain. This little drizzle will be the first of six rain events we endure while mushing the Iditarod… in March… in Alaska. I get everything in the protection of my sled bag, haul my unused food and trash to the communal pile, and make my way to the cabin for my outer layers. As I go for my over boots, I realize they are no longer hanging where I left them. In fact, they are not here at all. I quickly look out over the parked teams, as if my boots will somehow jump out at me. I then turn my attention back inside, and analyze what other boots are still drying. There are another pair of Neos hanging on the opposite side of the drying rack, with “King” written in big letters across their side. I look outside again, and sure enough, he is gone. Figuring he is the culprit of my missing boots, I grab his and put them on. I am reassured of the mix-up, when I see that his are the same size as mine (although, much newer and in far better shape).

We depart Iditarod under heavy, overcast skies, and more drizzle. As we climb off the river and into the hills (which are seemingly endless at this point) the rain picks up, and soon we are mushing in conditions that remind me of my summers on the Norris Glacier. It is over 50 degrees, but amazingly, the dogs are moving nicely and seem to be handling the heat (and rain) with ease. My plan dictates a run through to Shageluk, about 55 miles. Although the trail and weather conditions are miserable, we stick to our plan and complete the run in about seven hours. The final couple hours of this run actually get quite pretty, and we enjoy some nice trail, and a beautiful sunset, as we climb our final series of hills before hitting the Yukon River delta.

Shageluk, an Ingalik Indian term meaning “village of the dog people,” is a welcoming community of about 150. They open up their community center for musher accommodations, and a lot of the village residents are spectating as we pull in. Rain has turned their main street into pure ice, and I encourage the checkers to help me park the team off the road and on a bank of the school grounds. A local man introduces himself and asks if there is anything else I need, other than my drop bags and straw. I point him to my sled drag and ask if he has a drill and some bits. He is delighted to be of service, and assures me he can help. I get the team cared for and my water heating, and quickly, my new friend is back with his whole drill set in tow. I get my knots untied from my temporary setup, and we get my drag reattached in its original fashion. Very cool! (Outside assistance is allowed in some sled repair cases, per the race judge).

I have declared my mandatory eight hour rest in Shageluk, and after a brief phone call to Katti, lay down for a longer nap (almost three hours!). I have a dream about mushing, of course, and when my alarm goes off, find it very difficult to sit up. The short sleeps are finally starting to get to me, and once up, I spend about five minutes just sitting. My alarm goes off again, and I manage to get to my feet and get dressed to feed the dogs. Everyone in the team is perky and ready for more food, and Qarth, who has been in single lead, even surprises me with a few barks!

Our run from Shageluk, through Anvik, and up to Grayling, is pretty straight forward. It is almost all flat, with the exception of a few overland portages to reach the Yukon, and the dogs cruise along with ease. About ten miles from Grayling, we hit the open and exposed part of the “Mighty Yukon” for the first time. There is almost always wind on this stretch of river, and a 15 mile per hour breeze is what greets us in the early hours of day six. Typically, our dogs do great in wind, but I sense a little hesitation from the team. I welcome the wind by calling out and talking to them about how great it feels, and my positive energy seems to give them a little reassurance. Whiskey, with his incredibly dense coat, welcomes the cool down, and gives a little more into the harness.

After getting parked in Grayling, we receive our full vet check (standard for every checkpoint that we stop in). The vet notices a little fluid buildup in Fierce’s lungs, and I am able to get her to cough by clapping on both sides of her ribs. This is a classic early sign of pneumonia, and “vet A” goes in search of “vet B” for a second opinion. I continue with my chores and hear a little hack from Fierce as she finishes her meal. At that moment, I know she has to be dropped, and left in the care of the vets. They return, and then agree on the diagnosis. Knowing that pneumonia is one of the top reasons for dog fatality, I don’t want to take any chance of her condition worsening. I am discouraged, however, as I had planned to drop Knox, and either Kelly, or Jane. Knox has not regained his full appetite, and Kelly has been giving me some signs that she is not enjoying the rough, slow trail. Jane, being the youngest and least experienced member of the team, is having moments of being overwhelmed by the whole Iditarod experience. If I were to drop these three concerns, and Fierce, I would be down to six dogs (an unreasonably small number at this point in the race). I give Katti a call to mope about our predicament. She suggests sleep, and I lay down for a few hours.

After a nap, things suddenly look a little better, and both Kelly and Jane are perky and upbeat, and Knox is ready for meal number two. I chat with a couple of my fellow competitors, realize we are all facing similar situations, and decide to pack and press on. The dogs show me their willingness by jumping off their straw, and holding all pee and poop until fully out of town (all those meals and snacks have to go somewhere!).

We have reached the point in Iditarod where it takes the team a full ten minutes to warm up and find their rhythm. Each dog must poop (a few times), and pee. They have to shake off and stretch out. A few must check in with their partner for encouragement. So on, and so forth. My team is definitely moving nice, and eager to get going, but they still must go through their whole warm up procedure. Our departure from Grayling is no exception, but the team seems to find their stride a little faster than normal, and within three or four minutes, everyone is rolling nicely and working at 100 percent. Jane and Kelly seem happy with some flat, smooth trail, and Knox is energetic.

I have made the decision back in Grayling to deviate from my plan A, and pack to run the Yukon in three segments as opposed to two. A straw bale sits on my cooler (just behind me), and a full meal and a variety of snacks are loaded in my sled, along with fuel for my cooker. The dogs are looking good, and for a moment, I consider throwing my straw bale off, and going back to plan A (a roughly 60 mile run to Eagle Island). I decide against this, however, and figure a little more rest will only benefit my team later on, and I remind myself that we are just over halfway into the race.

Because of warmer than normal temps this winter, the trail runs a little closer to shore, and we crisscross the river, avoiding open sections of water. After about five hours of travel, I start looking for a convenient spot to camp. There are a few considerations that are especially important when camping on a wide open river. The first of which, is trying to find a place somewhat out of the wind. Remarkably, the typical “breeze” of the Yukon is almost non-existent this night, and I quickly find a nice spot that meets my next two items of importance: a nice snowmachine track that leaves the main trail, but quickly returns (giving us a comfortable parking spot off the race trail, but with a clear path back to it); and plenty of soft snow that will be great for melting into water, but also make a cozy bed for me to sleep in (throw down my sleeping bag, in a bivy, and voila!).

I call the dogs onto the snowmachine track, and in another 50 feet, we are parked and the dogs are munching a snack. As I go through my chores, I notice that we have camped right next to an old fishcamp, complete with a small log cabin (unique for this lonely stretch of river). There is also a wide open section of flowing water, only about 60 feet out from our camp. Although a little unnerving, the ice is solid where we are parked, and the sound of moving water is actually quite peaceful.

A couple teams move by; Robert Redington with a smooth, fast moving group, and my buddy Aaron Peck, who had been a little discouraged back in Anvik, but seems to be moving nicely and feeling good at this point (the “highs” and “lows” of Iditarod emotions). A father and son from Grayling snowmachine up, and stop for a minute to chat. They are bringing some vet supplies to Eagle Island (an uninhabited tent camp), and also have an AR-15 rifle in case they see any game out on their midnight run. They get moving after a few minutes, and will come blasting back by in an hour, once I am done with the dogs and have settled in my sleeping bag.

Our next leg up the Yukon is best described in two parts: Pre-Eagle Island; and Post-Eagle Island. The “pre-Eagle Island” portion of this run flies by effortlessly. The dogs cruise a smooth trail in the earliest hours of morning, and in no time we see the lights of the island checkpoint, and climb off the river. We only spend a couple minutes here, grabbing food, fuel and supplies (well, actually, I start leave without fuel, and hit the brakes just as we are about to drop back onto the river). As I am fumbling with a few Heet bottles, Richie comes over to me and asks if I have heard about the upcoming trail conditions. “No, what’s up?” “They are saying overflow all the way to Kaltag.” I laugh, because that is about 65 miles, and that amount of overflow seems a bit ridiculous. The checker interjects, and says she snowmachined down that night, and it was at least 30 miles of water. I shake my head and jog back to my team, knowing either way, we have to keep moving. This then brings us to the second part of this run on the Yukon: “Post-Eagle Island.”

After dropping back onto the river ice, we mush a groomed airstrip, and at the end of this, almost immediately hit water. Nothing to dramatic, just a soggy hole in the trail about the length of a team, and maybe a few inches deep. The dogs run to either side of this feature, and the sled flows right through. Another 50 feet down the trail, we hit a similar patch of water. And then, another. Pretty soon, the trail starts to split into multiple braids, all full with water (some as deep as 16 inches). I have had the team running with no necklines, and the dogs are only attached by their harness to the gangline. This gives them a lot of freedom to move around, and coincidentally, avoid the deepest sections of water. Qarth is running in single lead, and has a good grasp on the best trail. He seems to be picking the path with the best footing and shallowest water. I still keep my attention fully focused on the trail ahead, and eventually have to pause my audiobook.

The water continues. It is not only wet, completely soaking my supposedly waterproof boots, but is also very unpredictable. Some sections, the water has refrozen, and is glare ice. Other spots have a thin layer of ice, which then gives way if the dogs and sled try to cross. Almost every wet spot has an incredibly slick edge, and both the dogs and I end up dropping into the majority of the pools we try to avoid. When, after an hour of this travel, we stop for a snack break, I find that the edge of the trail is just as wet. So, in a spot with no trail, you walk a few steps and then look back to see that every foot print is full of water. Super gross!

Overflow! For miles…

Hours of this travel starts to wear on us (me more than the dogs), and I decide to start searching for our second camp site, a little earlier than planned. At mile 40, we see a nice pulloff that climbs a piece of shelf ice, and gets us out of the water. I figure this is going to be our best option, given the conditions, and the dogs are eager to take the command and leave the slop for a bit.

Our rest is quite peaceful (again, no wind!), and the dogs get the most out of their four hour rest. It does rain for a brief moment as I am packing the sled. But, only briefly, and the dogs shake it off. Because I have stopped a little sooner than planned, we are now looking at about a 48 mile run to Kaltag. This is a little longer than the first two legs, but I am hoping that the checker is correct, and we will soon leave some of this water. While resting, we are passed by about 6 teams, all running straight through from Eagle Island to Kaltag (65 miles). Although this had been my original plan (which I deviated from back in Grayling), I feel affirmed with every passing team, that I made the correct decision to add in another rest. The water, and slow nature of the trail, has slowed a lot of teams, and this run will take most of them almost 10 hours to complete (which, in turn, will affect their speed later in the race).

Our rest comes to an end, and I finish booting the team right as Martin Buser rolls by. I call the dogs off their straw, and we give chase. The dogs go through a brief warmup, but are almost immediately moving at seven miles per hours. Looking back, I see that we have pulled out only a hundred yards in front of Robert. Although we are just getting warmed up, we keep our distance from his team, and tail Martin for the next couple of hours. We leave the overflow! As a tradeoff, we are met with a decent headwind, and our speed drops as the trail becomes softer, and more drifted. Martin stops to snack and we roll by.

The trail becomes far less obvious, and soon disappears all together. Our speed is now about five miles per hour, and I decide the GPS is no longer helpful and shut it off. Qarth is undeterred by the conditions, and continues to drive forward, as happy as ever running by himself. Knox, however, is not handling the slow trail very well, and has started to lay off his tugline (completely unheard of for him). This is a clear sign that he is truly tired, and I know that I am going to have to load him. We make it another couple miles until I can find a spot out of the strongest wind. We stop. Martin and Robert both go by as I give everyone a snack. I know that this will be the last I see of them on this run, having to add a 65 pound dog to the sled. Knox is content to be loaded, and immediately makes himself comfy on my parka at the bottom of the sled. We get moving, and I am now pedaling and ski poling in earnest to keep our speed.

A mile after loading Knox, the trail improves dramatically, and I can actually pack the ski pole away. The eight dogs on the line are working nicely, and based on my memory of the trail from last year, I gather we are about seven miles from Kaltag. I check my watch and estimate that we are about 26 hours ahead of last year’s race schedule. This helps to further boost my spirits (along with the trail improvement), and I can actually sit down on my sled for a minute and scratch Knox’s ears. I know he is out of the race at this point, and will need to be left in the upcoming checkpoint. I am bummed on many levels to loose Knox from the team. He is a finisher from last year. He is a strong and smart leader. He is probably my favorite dog, whom I am most bonded to. But, all of that being said, for my hardest worker to no longer want to contribute, leaves no room for second guessing. It is clear that he needs a break, and a chance to rest up for more trips in the spring. I know that he will be back for more Iditarods, and this helps me deal with his departure from this race.

In Kaltag, I have a chance to razz Jeff about our boot mix-up. He is packing his sled as I pull in. As I work on chores, I yell over to him, asking about the condition of his feet. At first he is a bit confused, and when I explain that he swapped our boots, he suddenly puts the pieces together. He tells me he thought there was something off about the pair he currently has on his feet. I laugh and tell him, “that yeh, those suckers are three years old and have about seven thousand miles on them. And, did you notice they aren’t waterproof?!” He gets a bit more charged up and exclaims, “My feet were soaked a half mile out of Eagle Island!” We have a laugh, and I offer to trade. But, his options aren’t great: Either continue on with mine, which are dry, or, take his pair back, which I have now thoroughly soaked. He opts to continue on, wearing mine.

The run from Kaltag to Unalakleet is really where my race starts to come together. I decide to continue on to the coast with “short” runs, followed by relatively short rests. I am still wanting to bank rest for a tough run around Norton Sound, but have also seen on the Yukon that my team’s speed is coming up with our current run/rest schedule. I opt to stop a few miles short of Old Woman cabin, where all of my fellow mushers will be resting, and break the 80 mile run to Unalakleet into two equal parts. This also keeps us away from the “competition” and any potential distractions. The dogs will sleep better, I will sleep better.

We have a nice break next to the trail, and I am surprised to not get passed by a single team. I try and remember who was still back in Kaltag when I left. I feel that there were at least three teams who should have been with me on this run. Another rain shower has hit while we have been sleeping, and as I pack my sleeping bag, water streams off of it. The dog’s jackets are also soaked as I pack them, but at least they have served their purpose and kept the dogs warm and dry.

Just as we are ready to leave, a biker comes by, pedaling his way to Nome. Yes, you have read this correctly. There are people every year that compete in a race called Iditasport, and ski, jog and bike the Iditarod trail to McGrath. A few crazy individuals have not had enough at that point, and continue on to Nome. They make surprisingly good time, and we will often leap frog joggers and bikers for an entire 36 hour period before finally slipping away from them.

Anyways, this biker pauses for a brief chat, and then continues up the trail. He makes for a nice chase tool for the dogs, and I decide to put Forty in lead, with Qarth, for the pursuit. We catch him just past Old Woman, and we leap frog for the next 25 miles. This adds some entertainment to an otherwise boring run, and the dogs have a blast all the way to Unalakleet.

Our arrival into the checkpoint, is met by a small group of cheering spectators and villagers. The dogs, acting like the pros they are, take the welcoming group in stride. I am initially thrown off by the fan-fare, but quickly regain composer and follow a volunteer to our parking spot. There is one word that comes to mind when I think of parking in Unalakleet, and that is “kids!” Children abound, and the parking area is their favorite playground during Iditarod. Our team is suddenly positioned in the middle of a battlefield between two rivaling factions of 2nd, 3rd, and 4th graders. Trail markers are their weapons, and the bails of straw and drop bags are their bunkers. Pretty wild! But, at least I am somewhat prepared, and have some candy to distract them. I can get a few to convince the others to move their conflict on down the yard a little ways.

Another thing that comes to mind when I think of Unalakleet, is food. There are multiple villagers that cook meals to order in the community center, and mushers can eat as much as they want. I strategically sent only one of my personal meals here, and plan to load up on bacon (having made it just in time for a late breakfast). So, after feeding a team that eats like champs, I take my soaked gear to the center and take advantage of a real clothes dryer, a half-pound of bacon, and a private room for a good nap.

The Unalakleet communications center is also located right in the main room of the community center, and for the first time in a few days, I can get an accurate look at the entire race (using the tracker and all!). I am still focused first, and foremost, on just making it to Nome. But, I also know that I have a nice eight dog team that is moving quickly and ready for the coast. I have, at this point, thrown out my schedule. So, I do a little math while looking at the tracker, and put into memory how far in front the next five teams are, and how fast they are traveling.

The dogs eat a second meal with vigor, and I spend a minute joking back and forth with Seth, who is parked behind me. Reaching the Bering Sea coast is a monumental feat in the Iditarod experience, and it tends to lighten the spirits of every musher in the race (if only for a few moments). I feel confident as I get things packed to leave, and with Seth departing 30 minutes in front of us, we now have someone to chase.

Unalakleet to Shaktoolik is 42 miles, running primarily through the Blueberry Hills. They are HILLS! We have a chance to get warmed up, running a slough that borders town, and then we are climbing. The ascents start off fairly gradual, but after an hour or so, become pretty intense. With an eight dog team, it is essential that I run, pedal and ski pole up every hill. Every so often, we catch a glimpse of Seth’s headlight, far off in the distance, and far above us. The climbs seem to go on forever. I lose a ski pole as we descend a steep hill, but luckily, I have another. Snow is non-existent on a few lakes, and we struggle to stay on the trail with a strong side wind (normal for this coastal region).

We leave the hills after about 30 miles, and run a wide slough into Shaktoolik. It is also barren of snow, and there is a west wind that pushes the team towards a snow covered sea wall. Qarth, in single lead, thinks the sea wall is a good option, and I know the middle of the slough is the better option. We agree to split the difference, and run a few yards out from the sea wall, on a slightly less-than-level angle of pure ice. The “trail” (scratch marks in the ice) splits, and markers go both directions. I let Qarth choose, and we quickly ascend the wall next to us, and are running a plowed road. It is snow covered, though, and I am happy with the decision. This takes us into town, and to the two sleep deprived checkers waiting our arrival.

We park just behind Seth, and get a slight break from the forceful west wind. There has been a mix-up with my drop bags, and I am missing my bag number two, which is the bulk of my meat. In food drop prep, I had sent an extra drop bag of food to Shaktoolik, knowing that weather could keep us hunkered down here for quite some time. (A few years back, the front runners of Iditarod spent almost an entire day here, waiting out a storm on the sea ice, separating the two checkpoints of Shaktoolik and Koyuk). Although I have enough quantity of food for the dogs, a large portion of the meat has spoiled in the warm temperatures (a problem we have been facing for the last 250 miles now), and I am missing almost all of my beef (as it was in bag number two). Seth is gracious enough to give me a ten pound bag of beef, and the dogs keep up on their protein rich diet.

My time is this checkpoint is filled with unease. I am thrown off almost immediately, when the vet who checks my team informs me that Kelly (who I know to be the fattest member of the team) is “skinny.” He does not elaborate. Simply informs me that small females have been struggling to keep weight (which I have never experienced in my years of mushing), and he is concerned with her. I finish what I am doing and take a minute to asses my entire group for weight (something I am usually doing inadvertently through petting, massaging, and basic handling). Although the whole group was just checked 8 hours ago, and they ate great on the way here, I am now a little unnerved (maybe I missed something!). Upon a full, hands on inspection of ribs, spine and hips, I am reassured that everyone looks good (and Kelly remains in the best shape, second only to Qarth). I scratch my head and try to forget about it. As I walk inside, however, there is an immediate feeling of tension.

I take off a few layers and look for some food (a village dog got into one of my other drop bags, and ate all of my personal meals). I learn that a few front runners of the race have had their teams quit running, and are now stuck out on the sea ice, or in a nearby shelter cabin. Another team was just picked up by snowmachine, and brought back to the checkpoint. One more team has returned to the checkpoint to scratch. People that are successfully making the run across, are averaging just over six miles per hour (on what is a completely flat trail across frozen sea ice). So, the checkpoint’s race judge has ordered the vets to give extra attention to all incoming teams, and weight is the number one concern at this point in the race. While all of this makes perfect sense, I still feel that things are getting a little out of hand. One of the teams just in front of me is pulled from the race, sighting dogs that are too thin to continue. I look at his team with him, and decide that it is time for me to get away from this checkpoint.

While I have the utmost respect for the vets that volunteer their time to the race, and know that they are critical for making sure every musher’s team is healthy and well cared for, they all have different backgrounds and different levels of race experience. I feel like this particular vet, operating in the middle of the night, is not making accurate determinations on the health of these teams. And furthermore, doesn’t know how to properly asses body weight and hydration. I avoid the conversation and debate taking place inside, and quickly put my layers on. I do, however, have to bum a half dozen sausage links from one of the gracious checkers, who is in the process of cooking breakfast for the race staff. She even gives me a waffle for the trail!

In traditional years, with average winter temperatures and storm patterns, the run from Shaktoolik to Koyuk is a straight shot across the frozen Norton Sound; town to town. This year, as with last year, the trail sticks much closer to shore because of unpredictable ice thickness, and storms that have washed up huge icebergs. So, the run is a few miles longer than noted on race maps, and involves a couple last minute reroutes.

We depart Shaktoolik just before dawn, and run the remainder of the slough we came in on. Just before it joins the sea, we turn off, and run overland for a few miles. It is slow going, and the snow feels like sandpaper. Everything is white, and there are no trees, rocks, sticks, or grass for definition. It is just wide open white, and quite dull for the dogs. Sunrise is pretty, and with the light, we can view the mountains outside of Elim, about 100 miles away. Mushing on, we come across the spot where Nic Petit’s team shut down, and can clearly see the indents in the snow from sleeping dogs, and food that was left behind. There is something quite earie about seeing the spot where a person’s mistakes have come to a head, and their team has decided, on their own, to bring the whole race to a screeching halt. I keep my dogs rolling, and remind them how good they are doing.

A mile or so later, we pass a friend, Matt Failor, holed up in a shelter cabin on the edge of the sea ice. He has been stopped for about 20 hours, and is now out of the cabin and eager to get going. We exchange a few words as I go by, and he tells me he is waiting for a team to draft behind. I tell him I can’t afford to stop at the moment, and wave goodbye (my fear being that his team would not immediately chase, and if I were to make too many little stops to wait, my team would decide it is a good time to lay down for a mid-morning nap). My team is not tired, but dogs are very subject to “group think.” If other teams have been struggling in this exact spot, and there is a team directly behind them that is struggling, they may feel that energy, and the slow trail conditions may help make up their minds to sit down. I am also on edge about this run, starting with our experience back in Shaktoolik, and the dogs sense that energy as well. So, I just want to get across the ice as quickly and smoothly as possible. As a musher, I always have to put what is best for my team, and my race, first. At this moment, unless someone’s life is in danger, we are going to keep moving.

We mush a few miles of punchy trail, water seeping into our tracks as I look back. The trail improves slightly, and we pass another spot of an unplanned “camp” by a team in front of us. Jane grabs a giant piece of meat as we go by, and I stop to pull it out of her mouth and break it into smaller pieces to share. I chuckle about their crazy appetites, and toss a piece of meat to the dogs that missed out on Jane’s plunder.

The breeze encourages Qarth to leave the marked trail, and we discover that the sides of the trail are windblown, glazed snow, and therefore much smoother traveling than the trail itself. Our speed picks up by over a mile per hour, and I let Qarth pick his own path. I keep the trail markers to my left, and don’t let them get out of sight. The sea ice has holes and cracks, pressure ridges and jagged icebergs, so leaving the trail is not always the best idea. But, at the moment, the speed increase seems worth the risk, and we move along nicely.

The steady breeze continues to push Qarth’s direction gently towards shore, and every few minutes I have to call him “haw,” back out to sea. I spend a minute, verbally getting him back on track, and can then be silent for a few minutes. After an hour of this, I see that the “gee, haw” commands are starting to demoralize the team, and I call us back to the marked trail, trading out speed for consistency. Although this trail is slower, it is obvious to follow, and won’t tax Qarth’s head. At four hours into an eight hour run, 750 miles into a race, this is an important consideration to remember.

We pull into Koyuk in the heat of the afternoon. The dogs have now taken to screaming and barking as we get into a checkpoint, and they give a nice little show as we are guided to our parking spot. We have gained a few minutes on Seth during this run, and Kristy and Anna are still finishing their first round of chores as my dogs stretch out on the ice. Wade is getting ready to pull the hook as I light my cooker, and he compliments my small team. Kelly, who I bought from him, is in wheel, and I tell him she has been quite the cheerleader on the coast. She has finished three Iditarods with Wade, and surely knows that Nome is only three runs away now. He laughs, and says she can come back into his team. I get a chuckle out of that, and I wish him luck in his remaining race.

Once the team has cooled off and eaten their snack, I lay out their straw and get them comfortable in the sun. If it is cold, or the weather is inclement, dogs will sleep in a ball to conserve energy and heat. However, if it is sunny and warm, they will choose all kinds of positions while sleeping (often reflecting their personality and level of comfort with their surroundings). Qarth and Forty, always a little more apprehensive and alert, are sleeping in loose, protective balls. The rest of the team, however, is in some state of complete relaxation. Braavos and Mereen are both stretched completely straight, and laying on their backs, as if sunning their bellies. Frito, who is laying on his side, makes a nice pillow for Jane, who is stretched perpendicular to the gangline. Kelly, completely buried in straw (her favorite thing), is stretched out on her side as well. Whiskey looks something like a dairy cow, laying on his stomach with his legs tucked underneath him. He is wide awake, and patiently waiting for his second meal, which is still a couple of hours away (he just finished his first meal ten minutes ago, but has forgotten already).

Based on the standings, and run times of teams behind us, we are secure in the top 20 as long as we keep moving at our current speed. My original plan, had been to stop for four hours at each of the coastal checkpoints. However, with trail conditions that are making run times half again as long as “normal,” the dogs are needing an extra hour or two at every stop. I figure that six hours here will be adequate, and should set us up for a strong night run.

Kristy and Anna get a 30 minute head start on Seth and I, who basically leave together. These guys, have some additional rest on my team, but at this point, an extra hour does not really affect team speed. I doubt that I will see “the twins” on this run. Talking with Seth, I know that I will pass him almost immediately outside of the checkpoint. He is struggling with a couple females in heat, and his leaders aren’t overly motivated to charge down the trail. The plan is that he will get moving, and then use my team for his dogs to chase after I pass him. This works out well, and he follows me almost the entire way to Elim.

The first third of this run is quite hilly, and we are able to catch sight headlamps on the first ascent, about five miles out of town. I am surprised to see lights, and now get excited that we might catch Kristy and Anna on this run. Doing the math in my head (run speeds vs. trail distance), I know it will be close. But, I also have to watch my team and not get too caught up in the “race.” If a pass happens, great! If not, that is fine too.

Descending out of the hills, the trail runs out into a wide flood plain. As soon as we start out into the open, the wind hits us, and we are almost immediately in a strong blizzard. The wind is at our back, and the sticky snow is embedding itself in everything, including the dog’s fur. Soon, a black Whiskey, is almost completely white. Visibility goes in and out, and at times I can’t see past the wheel dogs, just in front of the sled. Once in a while, we catch a break, and I see the lights of the Beringtons in front of us. Distance is impossible to gauge, so they could be as close as a couple hundred yards, or as far out as a couple miles. In this time, we pass a shelter cabin along the trail, and a couple cheering snowmachiners standing out in the blizzard. It is a bizarre encounter, and I have to check myself a few times to make sure I am not hallucinating.

Towards the end of this flood plain crossing, we reach a spit, and mush onto an unmaintained road. It is at this point that we catch Anna. She pauses to let us roll by, and I shout out a quick thanks. A mile or so up the trail, we pass Kristy, who is stopped and waiting for her sister. The dogs are feeling great in the wind, and are having one of their best runs of the race. The three times that I have run this race, there has always been one run that sticks with me as the high point of the race (for team performance, overall ease, exciting terrain, extreme challenge, etc.). As we make this run to Elim, I know that this is “that run.” Everything seems to have come together to create that near perfect experience. I know in this moment, that we will not only make it to Nome, but make it there in good health, and in good form.

Elim is a quiet checkpoint early in the morning. I am the first in my group to arrive here, and as we park, I see there is only one other musher here. Matts Peterson is resting, after attempting to leave with Wade in the middle of the night, and then turning back to the checkpoint. Apparently, it was storming as severely on the north side of Elim, as it was on the south (where we were running just a couple hours earlier). Matts describes a trail that is completely blown in, with winds that were too strong for his leaders. I realize that he is a musher that I am moving faster than, and will be able to possibly stay in front of on the run to White Mountain. I decide on a five hour rest here, knowing that time will be sufficient for my team, but also competitive for the teams around me. I am reassured of my decision, when I step out of the fire hall (the building serving as headquarters) to an entire team that jumps off their straw, and gives me their full attention.

As I feed the team their second meal, Matts and I chat about the upcoming run. It is incredibly hilly for the first 25 miles, and if the trail is completely snowed over, and drifted, it can be very difficult for a single team to run. Often times, mushers will tackle a challenge like this by leap frogging back and forth (as one group of dogs gets tired of breaking trail, the other team can step up and take over for a time). We decide to try and leave together; my peppy team helping guide his out of the checkpoint, then trading off with trail breaking as we hit the biggest hills.

Knowing that this run will probably be the toughest of the entire race, I decide to leave Jane in Elim. She has been doing a great job, but I worry that the long climbs, through deep snow, will be more than she can handle on her first thousand mile race. At this point, she is the only rookie on the team, and aside from Frito, the only non-Iditarod finisher in the group. As she walks off with the vet, I see that Seth, nor the Beringtons, are up and moving yet. This is a good sign for holding our position on the way to Nome.

Finishing with booties, and getting the last items in my sled, I am asked by the race judge if I want help guiding my dogs out of the parking lot. I shake my head and tell her that they are feeling good and ready to go. She gives me a skeptical look, and informs me that no team has made it past the first snow bank (where every dog wants to stop and relieve themselves). I laugh, and inwardly plan to be the first team to make it past that obstacle without a stop. I have the utmost confidence in the dogs at this point.

I check in with Matts, and once I get his thumbs up, pull the hook. Qarth is in forward drive immediately, and I am riding the drag at mile 820. I smile as we round the 90 degree corner that has stymied the teams in front of us. Suddenly, the entire team is a single ball. I am dumbstruck for a brief second, and then see that the swing dogs have gotten tangled in a huge snowball that has stopped Qarth, and balled the remaining dogs. It is a BIG snow ball (picture a rounded wheelbarrow), and I have to hop off and pull the dogs around it. Well, Damn!

In all the fuss with our tangle, I completely forget about Matts. I have pulled the hook without thinking, and left him back at the checkpoint. We run right through town, climbing up towards the city airstrip, and as I look back, I see no sign of him. I feel bad, but recognize we all have our own race to run, and move forward. As we depart the road grade, and turn across the end of the airstrip, Qarth is met with a three foot deep snowdrift. I encourage him forward, and he leaps and bounds through the neck deep snow. This is a good sign for things to come, I think.

The ascent out of Elim is immediate, and unrelenting. There is also no room to get off your sled and pedal, run or ski pole. So, I stand patiently on the runners, and watch the dogs slowly climb. There are tight turns, a few drops, and a lot of uphill slogging. Any sign of Wade’s team is completely gone. We are breaking trail through a few inches of fresh snow. But, at least the skies are clear and the wind is only a gentle breeze (at least in the trees). Finally, the climb becomes so steep that I have to get off and run, pushing the sled slightly off the trail so I have enough room for my feet.

We reach the first peak outside of town, and I stop to give us a breather, and take a video of the surroundings and my wonderful dogs. They wag their tails and eat some snow, and then we are back to moving. I will not elaborate on every hill, but will say that I got my work out on this leg. I run and ski pole for the next four hours, as the team trudges through snow, which is at times belly deep. I have stripped down to only a hoody, and have no gloves and no hat. My thermometer says that it is above 40, and at times we are barely making more than four miles per hour. Nome suddenly feels a very longs ways away.

We conquer the hills after about five hours (that is an average of five miles per hour, for those of you paying attention to the numbers), and drop down towards Golovin Bay, and the town of Golovin. I have been struggling to keep the team on the trail (everything is a flat white, with no definition), and have started to play “musical leaders.” Qarth, after starting to weave back and forth, has been replaced by Braavos, who didn’t want Forty behind him, but also not next to him. Forty has led by himself for a short time, but really needs a partner, so Mereen has stepped in for a spell… I take a snack break.

Every dog gets a moment after their snack to roll in the snow, and Frito has decided this looks like a good spot to camp (it is 2:30 in the afternoon, and the sun is blazing). I adjust a dog or two, and also take a moment to clear my head and assess. I have brought food and provisions to camp if needed, but do not want to park the dogs without straw, or give up our current position. I put Qarth back up with Forty, and decide this is going to work.

Our speed towards Golovin is by no means record breaking, but the team is moving and the houses of town are slowly getting closer. This is one of the more stressful points of the race for many mushers. The town of Golovin sits only 15 miles from White Mountain. It is not a checkpoint, and has no amenities for mushers. Yet, we run right through the middle of their town, and front runners of the race are often inundated for autographs and pictures. I realize, with apprehension, that I am now almost a “front runner,” and may be stopped by a group of people who want to say hello. This would send the signal to the team that we have reached a checkpoint, and resuming our run may be quite difficult. I stress all the way to town.

In the end, my worry is unfounded. As we approach the ramp into Golovin, Qarth and Forty kick into overdrive, and start loping. I gather that Forty is excited to see if there are loose dogs, and Qarth is hoping to get through town as quickly as possible. The rest of the dogs vibe off their energy, and double their efforts to move forward. We lope through town at about ten miles per hour. There is not a soul to be seen as we go through, and within 45 seconds we are dropping back onto Golovin Bay. I give the dogs an “easy” command, and slow us back down to a conservative trot. The team seems very happy to be on the other side of civilization, and everyone keeps their head pointed forward. The remainder of our run to White Mountain is smooth, and our speed continues to climb as the evening temperatures cool off.

In White Mountain, teams park on the Fish River for their mandatory eight hour rest. The town itself populates a steep hillside, and the walk to the community center is one of the toughest climbs of the whole race. With the team fed and bedded down, I scale the hill to get some food and rest (oh, and my mandatory drug test before the finish). Inside, I spend a moment talking to Wade, who is putting on his boots to leave. The tracker shows that many of the top ten are still making their way to Nome, and a few have been on route for almost 14 hours (and are still a couple hours out of the finish!). Wade seems a little anxious about the next 70 miles, but we both know the only option at this point is to mush on, and see what you find. I wish him luck, and lie down for a couple hours of sleep.

After giving the team there second meal and repacking my sled for the final run, I head back up to the center for another bit of food and some coffee. I spend some time talking to Matt Failor, discussing the highs and lows of this year’s race. He spent much of the race in the top 15, but with his unplanned stop outside of Shaktoolik, has dropped back to 20th in White Mountain. I don’t get the exact details about his decision to stop for so long, but make my own inferences.

At last, it is time for us to get moving, and I get the team booted and ready for their run. With five minutes to spare, I lead the dogs off their straw and to an official “start line,” that points us out of the checkpoint. This is unique to White Mountain, and gives the team the opportunity to poop, pee and shake off. The checker gives us a countdown, and at zero, I pull the hook. Our takeoff is not as thrilling as the start all the way back in Willow, but the dogs immediately start rolling down the river, and look smooth and limber.

We run Fish River for about two miles, and then climb onto a long swamp, running west towards the Topkok hills. That’s right, there is another series of climbs that separate us from the finish of this damn race. There is absolutely no wind, and the temperature is about 18 degrees. It is nearly perfect for me as a sled driver, and feels relatively cool for the dogs (when compared to the temps of the majority of the race). We all seem to be enjoying the trail, although it is still slow and punchy from earlier winds and limited travel from snowmachines, or other dog teams (we are in 15th after all!). The aurora is out. This is another place in which I think about how lucky I am to experience this trail, and this incredible state of Alaska, all by dog team.

The Topkok Hills are no picnic to run, and some of the climbs would take an untrained teams breath away. Luckily, every team that reaches this point in the race, is well traveled, and well versed in climbing (one way or another). This year, I tried counting the number of significant climbs until we reach the coast outside of Nome, and I came up with 13. A few are so long and steep, that on approach, I initially confuse the trail markers for stars. The seven members of my team are strong, but a few steep climbs require me to actually push the sled from behind (at least to keep our nice speed and rhythm).

After about four hours of running, I calculate that we have been averaging just under eight miles per hour. This is about the fastest we have traveled in the entire race, and I start thinking about trying to really let the team open up in the last 22 miles, attempting to win “Fastest time from Safety to Nome.” This is an actual award that is presented each year to the team in the top 20 that can run into the finish at the fastest speed. I know that Wade will be attempting this, as he has a pretty fast team with a decent amount of rest. But, as for the other teams in front of us, I know that they have all hit bad weather and slow trail conditions. I am traveling faster than the teams behind me. I stop to give some clear water to Qarth and Whiskey, who both have started to dip a little snow from the trail.

At mile 26, we descend out of the hills, and pass a safety cabin just before the infamous “blow hole.” In preparation, I have sealed my gloves, donned my neck gator, and pulled up my hoods. Even though the hills have had no wind, the blow hole can be in a completely different weather system. As we go by the cabin, and start to parallel the beach, there is not even a slight breeze. I slowly relax, and then decide to sit down on my sled. Although I have had my “tail dragger” this entire race, I have sat down for a total of about 12 miles. Now, I open my snack bag and munch on some dried fruit. I change my playlist, choosing some of my favorite tunes. The experience is entirely unnatural for this part of the race, and I feel almost a little cheated.

I am riding the drag very lightly, but eventually start to nod off with a lack of stimulus from the trail. Although the trail is obvious, and the dogs are chasing the glow of Nome (still more than 35 miles away), I don’t really want to fall completely asleep. I decide to pedal just for something to do. The dogs are now rolling at what seems to be a comfortable speed, and we are averaging between 7.5 and 8.5 miles per hour. I am pretty sure at this point, that we can compete with Wade for the “Safety to Nome Award.”

The trail eventually joins a summer road to Teller, and we are now passing highway mile markers. Light has just started to creep over the horizon, and the arrival of dawn, has ptarmigan on the move. Every quarter mile, the dogs spook up a group of 20 or 30 birds that explode from the side of the road, and fly across the trail. Forty, always in the hunt, and host of the largest prey drive of any dog we own, is loving the action. He is attempting to take the team at 12 miles an hour down the trail, and I am having to fight against him with the drag. Our speed is basically surging every few minutes, and the dogs are going to slowly wear themselves down. I make a stop, give another snack, and move Forty back a position (to be replaced with Braavos, who is far too serious for birds).

We cruise into Safety and get checked in. Kale is there, doing some filming of my team. He has snowmachined the whole trail, and I have seen him, off and on, for the last hundred miles. I alert the checkers that I am not ready to be “checked out,” and get off my sled to give every dog a snack and get their booties checked, and replaced if needed. I mess around for a couple minutes and then get back on my sled. The checkers hand me my bib, which I store in a pocket. I look at my watch, and tell them I am ready to leave. They give me my checkout time, and I look up to the dogs to see Kale standing in the middle of the team. No dogs have necklines, so if I move forward, he is sure to be tripped. I holler up to him to step away from the dogs. He starts towards the Safety Roadhouse, which encourages the dogs to follow him towards the building. They are sure that this is a checkpoint, which means that there is straw and more food located somewhere. Getting a little more agitated, I yell to Kale to walk the other direction. He is still filming, of course. I pull the hook, and now have to firmly command the dogs to “gee” back to the trail, and give them a couple strong commands to get moving and leave Kale behind. I am sure my agitation and annoyance have been saved to the archives of the internet somewhere…

We are back on the trail and moving, but our rhythm has been broken, and Qarth is now a little distracted by some snowmachines and an approaching helicopter (people from Nome have now woken up, and are coming out to watch our final miles into the finish). I figure we will get moving again in a minute, and pull out my ski pole to keep myself occupied. A few minutes later, Qarth starts dipping for snow, and his intensity distracts the other dogs. I know that he shouldn’t be dehydrated, considering he just had a decent meat snack, but nevertheless, I stop and offer him the last of my personal water. The snoot refuses it, and eats snow instead. I realize he is just pissed we didn’t spend more time in Safety, and there is nothing I can do for that. Resigned, I get back to the sled and take off, knowing that any chance of beating Wade’s time to Nome is out the window.

I focus my attention to enjoying the morning sunrise, which is spectacular, and looking out for more little animals, which seem to abound the trail to Nome. A few miles from Safety, we climb Cape Nome, a monstrous hill that separates Safety from the finish (as if to throw us one last challenge before we are done). The dogs climb nicely, but as we reach the top I can feel we won’t regain our smooth rhythm from earlier, and a couple dogs are a little on the dehydrated side. I am mad at myself for not packing a more water dense meat for this run, and make note for next year.

We stop a final time on the backside of the cape, Nome now in view. The dogs roll around and eat some more snow, and I give them all a pat on the head. The remaining 12 miles roll by, and as we climb onto Front Street, I feel overwhelmed with pride for my team. Then, Qarth bulks at the moving vehicles, sirens and groups of spectators, and I quickly jump off to move him back in the team. Braavos leads us for the remaining half mile.

I knew I was taking a chance with Qarth in lead, but was hoping he would handle the pressure and make it under the burled arch in lead. Although our kennel has many dogs who run lead, no team member comes close to Qarth for drive and dedication under tough conditions. For two Iditarod’s now, he has handled every single challenge with ease (usually tackling those portions alone in that position), and is always ready to leave his straw for another challenge.

The team comes under the arch in perfect form. I see Katti, ready to embrace Braavos as I bring the team to a stop. I am greeted by Mark Nordman, the Race Judge, and then asked for a quick interview from the Nome Nugget (the local paper). I answer a couple of questions, and then tell them to pause for me to give every dog a snack. I embrace Katti. My Mom (always supportive of my crazy adventures) is there for a big hug, and I get a high-five from her partner Noah. I congratulate the dogs, and pass out a few booties to people spectating at the finish. And just like that, the race is over.

Well, actually, that is not entirely true. We run our team to the Nome dog yard, and get every dog unharnessed and on their drop line. The dogs are analyzed by the vet team for body condition, flexibility and overall health (they are putting together notes for the “Vet’s Choice” award), and then every dog gets to relax in their flight kennel full of straw. It is early afternoon, and the sun is out. I mix up a meal for the team, and everybody eats with enthusiasm. Now, with the dogs fed and bedded down, I can get a break, and have breakfast and mimosas with the family. I know that in a few hours, the team could be ready to keep moving down the trail.